Stefik, M. (2024) AIs and Human-Compatible Values. DropBox Link (8 pages)

Stefik, M. (2024) AIs and Human-Compatible Values. DropBox Link (8 pages)

The vision of AIs as human-like collaborators is a staple of mythology and science fiction, where artificial agents with special talents assist human partners and teams. In this vision, sophisticated AIs understand nuances of collaboration and human communication. The AI as collaborator concept is different from computer tools that augment human intelligence (IA) or that intermediate human collaboration. Those tools have their roots in the 1960s and helped to drive an information technology revolution. They can be useful but they are not intelligent and do not collaborate as effectively as skilled people.

With the increase of hybrid and remote work since the COVID pandemic, the benefits and requirements for better coordination, collaboration, and communication are becoming hot topics in the workplace. Employers and workers face choices and trade-offs as they negotiate the options for working from home versus working at the office. Many factors such as the high costs of homes near employers are impeding a mass return to the office.

Government advisory groups and leaders in AI have advocated for years that AIs should be transparent and effective collaborators. Nonetheless, robust AIs that collaborate like talented people remain out of reach. Are AI teammates part of a solution? How artificially intelligent (AI) could and should they be?

This position paper reviews the arc of technology and public calls for human-machine teaming. It draws on earlier research in psychology and the social sciences about what human-like collaboration requires.

Stefik, M. (2023) Roots and Requirements for Collaborative AIs (24 pages) arXiv http://arxiv.org/abs/2303.12040

Today’s robots do not learn the general skills needed for such services as providing home care, being nursing assistants, or doing household chores. Addressing such aspirational goals requires improving how AIs and robots are created. Today’s mainstream AIs are not created by agents learning from experiences doing real world tasks and interacting with people. They do not learn by sensing, acting, doing experiments, and collaborating. This paper investigates what aspirational service robots will need to know. It recommends developing experiential (robotic) foundation models (FMs) for bootstrapping them.

Stefik, M. (2024) What AIs are not Learning (and Why) (16 pages) arXiv https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.04267

Developmental AI creates embodied AIs that develop human-like abilities. In a bootstrapping approach to developmental AI, the AIs start with innate competences and learn more by interacting with the world including people. Developmental AIs have been demonstrated, but their abilities so far do not surpass those of pre-toddler children.

In contrast, mainstream approaches have led to impressive feats and commercially valuable AI systems. The approaches include deep learning and generative AI (e.g., large language models) and manually constructed symbolic modeling. However, manually constructed AIs tend to be brittle even in circumscribed domains. Generative AIs are helpful on average, but they can make strange mistakes and not notice them. Not learning from their experience in the world, they can lack common sense and social alignment.

The paper below lays out prospects, gaps, and challenges for developmental AI. The goal is to create data-rich experientially based foundation models for human-compatible AIs. A virtuous multidisciplinary research cycle has led to developmental AIs with capabilities for multimodal perception, object recognition, and manipulation. Computational models for hierarchical planning, abstraction discovery, curiosity, and language acquisition exist but need to be adapted to an embodied learning approach. The competence gaps involve nonverbal communication, speech, reading, and writing.

Aspirationally, developmental AIs would learn, share what they learn, and collaborate to achieve high standards. They would learn to communicate, establish common ground, read critically, consider the provenance of information, test hypotheses, and collaborate. The approach would make the training of AIs more democratic.

Stefik, M., Price, R. (2023) Bootstrapping Developmental AIs (112 pages) arXiv http://arxiv.org/abs/2308.04586

When I was asked to lead the Intelligent Systems and Technology Lab at the Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), I wanted the lab to succeed wonderfully in its research mission. I was a fairly prolific inventor and had taken multiple tours of duty as a research manager. I set out to open my mind to possibilities for effective invention and innovation by interviewing colleagues at PARC and elsewhere about their best practices.

I shared insights from the inventor interviews with my wife, Barbara. Soon, she had her own recording device. She joined me on the interviews and did additional ones on her own. Three years later our work led to the publication of our book Breakthrough by The MIT Press.

One of the most interesting questions that we asked and sought to answer was “How do you create the conditions under which inventions arise?” We also asked “How do you create the conditions under which innovations arise?” The distinction is that invention is about developing ideas and innovation is about developing inventions to become products.

It is timely to ask these questions again. Today there are needs and opportunity not only for invention and innovation, but also for new technologies and ways of inventing and innovating.

PARC’s Colab (1989)

When I came to PARC, I loved the wall-sized whiteboards. We developed group processes of gathering at a whiteboard, brainstorming, and organizing our ideas. I wanted to speed up the process for rearranging the drawings and symbols on the whiteboard in our intense idea sessions. This led to a DARPA-funded Colab project where we created an electronic meeting room, including a wall-sized projected screen made touch-sensitive by special hardware from the Xerox skunk works.

Portable meetings and portable ideas were intermediated by interactive whiteboards

We invented WYSIWIS (What You See Is What I See) interfaces and public and shared windows. Our team productivity was accelerated by conversations that combined the familiar one-person-at-a-time audio channel of meetings with computer-intermediated visual elements. The tools also created digital outlines and other records of our work as described in our paper.

Our multi-user Colab tools worked best when we were in the Colab. John Seeley Brown and I saw a possibility (not then technically practical) for creating meetings and idea-structures that were “portable.” They could be resumed, rewound, re-branched, and extended. Our paper “Towards Portable Ideas” imagined how strategically-located interactive whiteboards with a suitable infrastructure could extend the utility and life of conversations as “portable ideas” were created, carried and refined by work groups. This idea on boards, tablets, and other devices is ripe to be realized today.

Design Lab created for the Technology for Agile Organizations (TAO) group at PARC

Colab technology led to a Liveworks PARC spin-out with a “LiveBoard” product, which was expensive at the time. Many years later, using off-the-shelf technology, we built a simpler design lab for stand-up meetings and working design sessions for a smart cities project. Meetings were BYOC (Bring Your Own Computer) and seating was at a stand-up table to encourage high energy interactions.

How could a virtual workplace support serendipitous interactions?

Forward to the COVID pandemic. Many workers had completed a year of desk-bound remote working. They practiced sharing screens in online meetings, having targeted side conversations with text messaging, and finding the mute button.

The pandemic has probably accelerated the shift of organizations to geographically distributed forms where teams work at different sites, and more employees work remotely.

But are the remote workers and teams as effective at invention and innovation? Are distributed teams and teams of teams less-powerfully connected and less effective? Are important opportunities being missed?

Despite long hours in meetings, it seemed harder to have the formal and informal conversations afforded by physical workplaces where ideas are seeded and developed.

A physical workplace offers affordances for informal interactions. Meetings around problem solving or idea development are open and attract opportunistic engagement. Consider a physical office workplace as in the picture. What are its affordances for:

A physical workplace offers affordances for informal interactions. Meetings around problem solving or idea development are open and attract opportunistic engagement. Consider a physical office workplace as in the picture. What are its affordances for:

Current online meeting software is focused on scheduled meetings. The meetings are often not serendipitous, engaging, or effective. Management has little visibility into collaborative engagement opportunities in the virtual workplace. It can not easily see how well today’s remote meeting tools promote collaboration and coordination. People talk about burn out from on-screen meetings all day long.

Especially in regions like Silicon Valley, the limited available land area has led to a dramatic rise in the cost of real estate. This cost creates substantial overhead for businesses and also challenges for new employees who want to buy homes and raise families. In this way, the local concentration of technology development is itself creating economic pressure for policies to allow remote workers. Do we need a new generation of infrastructure for distributed organizations?

Forward to today. I am the principal investigator of the COGLE (Common Ground Learning and Explanation) project. COGLE is part of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) eXplainable AI program. It is supported under contract FA8650-17-C-7710.

In writing up findings of a user study about XAI explanation I found myself reflecting on the Stanford DENDRAL project, which routinely solved complex chemical structure elucidation problems. DENDRAL had superhuman performance in solving chemical structure puzzles. Carl Djerassi, a Stanford chemistry professor and inventor of the birth control pill, was one of the leaders of the project. In his autobiography, Djerassi reported on a pedagogical experiment. He assigned his students in a graduate chemistry seminar to use DENDRAL to check the chemical structures that were reported in papers from peer reviewed chemistry journals. Without exception they found that every article had mistakes. The articles presented evidence and identified the chemical structures that were consistent with it. For every article, there was at least one structural alternative that the authors and reviewers had missed. The point is that combinatorial problems are difficult to get right, even when people check each other’s work.

COGLE’s domain is about autonomous drones that carry provisions in mountainous and forested settings to stranded or injured hikers. The connection here is that like DENDRAL, COGLE’s AIs have superhuman capabilities. They find optimal flight plans for missions in a simulation world. One configuration of COGLE is as a decision aid for humans, who choose the best AI-controlled drone for a mission. The AIs at hand have different experiences, know different things, and make different plans.

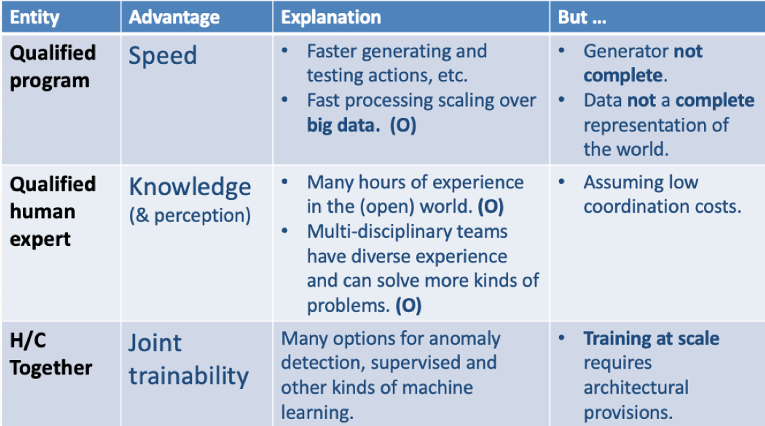

Typical advantages of human and AI cognition on combinatorial problems in open (O) worlds.

Although COGLE’s AIs are great optimizers, they are limited by the specific experiences in their individual training. The different AIs have different experiences and knowledge. User study participants had to judge when they should trust an AI and when they should not. Sometimes the human — or even the Explainer — can tell that the AI-generated plans have issues.

This application example frames one of the important uses for XAI technology: decision support. People and computers have different advantages and can complement each other on a human plus computer team. There are other cognitive asymmetries and applications as well and studies to understand where and when AIs can best complement humans. Matt Johnson and Alonso Vera make the case that the greater the power of an AI on a team, the greater is its need for skills for collaborating with people. Teaming intelligence is all about team members understanding, supporting, and exploring their interdependence in the partnership.

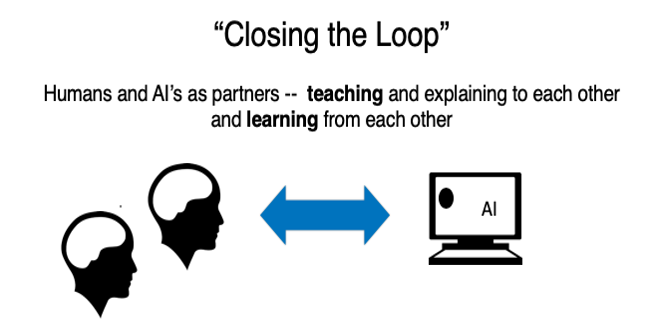

Closing the Loop refers to AI systems that can both explain and take advice.

At a principal investigator meeting of the XAI program I was asked to lead a panel about a research area beyond XAI called “Closing the Loop” (CTL). CTL casts XAI as half of a solution. An XAI has deep or other form of machine learning augmented by explanation capabilities. In the other half of a CTL, the AI takes advice and collaborates with people. Ideally, a CTL system can participate in a conversation with users, develop common ground with them, improve knowledge and performance over time, and be a collaborative computational partner. Another technical term for this idea is Interactive Task Learning (ITL).

The panel also considered the DARPA-hard research challenges in creating CTLs. Like XAI, CTL requires multi-disciplinary perspectives to create the AI and to understand the requirements for effective human plus computer teaming.

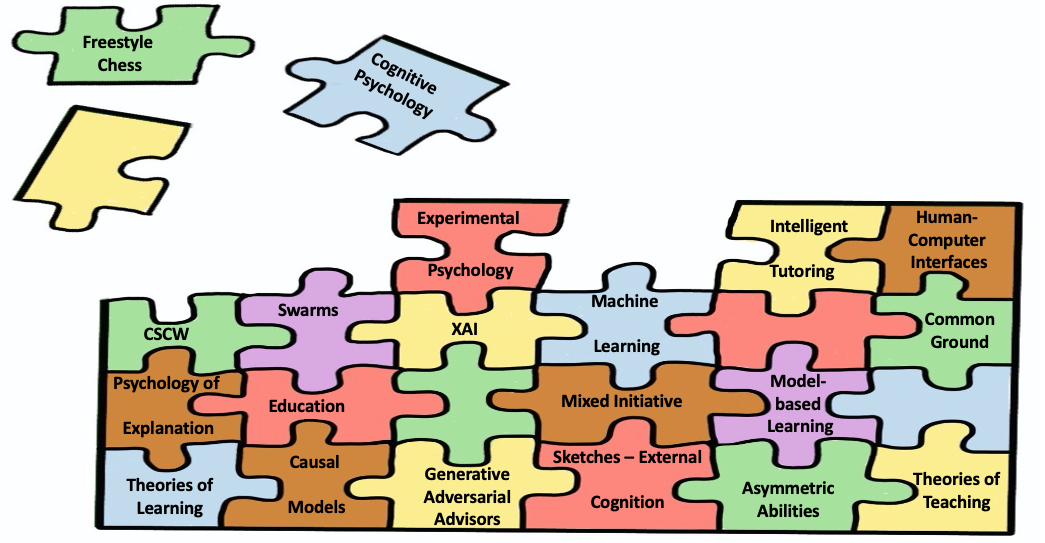

Disciplines and ideas as pieces for a CTL project.

In his bestseller book Leading Matters, former Stanford University president John Hennessy offered his thoughts on the nature of society’s big challenges — which include such issues as responding to the pandemic, energy, the fragile environment, and others. Such problems do not fall within single disciplines or have easy fixes. They are multi-dimensional and interdisciplinary. Even developing an understanding of such a problem does not fit easily in one person’s mind or their education and experiences. Shared purpose, collaboration and determination are required.

A recent call for action by the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence, (Final Report) advances a case for a large and sustained national effort for research and development of AI science and technology. This is another piece of an answer for our opening question.

This post started with the question “How do you create the conditions under which innovation arises?” In the years since our Breakthrough book was published, several things have happened. The world’s problems have become harder, and the technology has advanced. Our unaugmented human minds have not advanced.

Revisiting the question a decade and a half later, we see new opportunity in how to plan our collective journey. The journey involves new tools to support human collaboration in distributed organizations. It also includes developing AI partners to join the team.

Many thanks to Edward Feigenbaum and PARC colleagues for conversations in developing these ideas.

Post by Mark Stefik with contributions from Michael Youngblood

Human-computer teams combine best of human and computer cognition. The combination can lead to extremely high performance. But are human-computer teams the future of work?

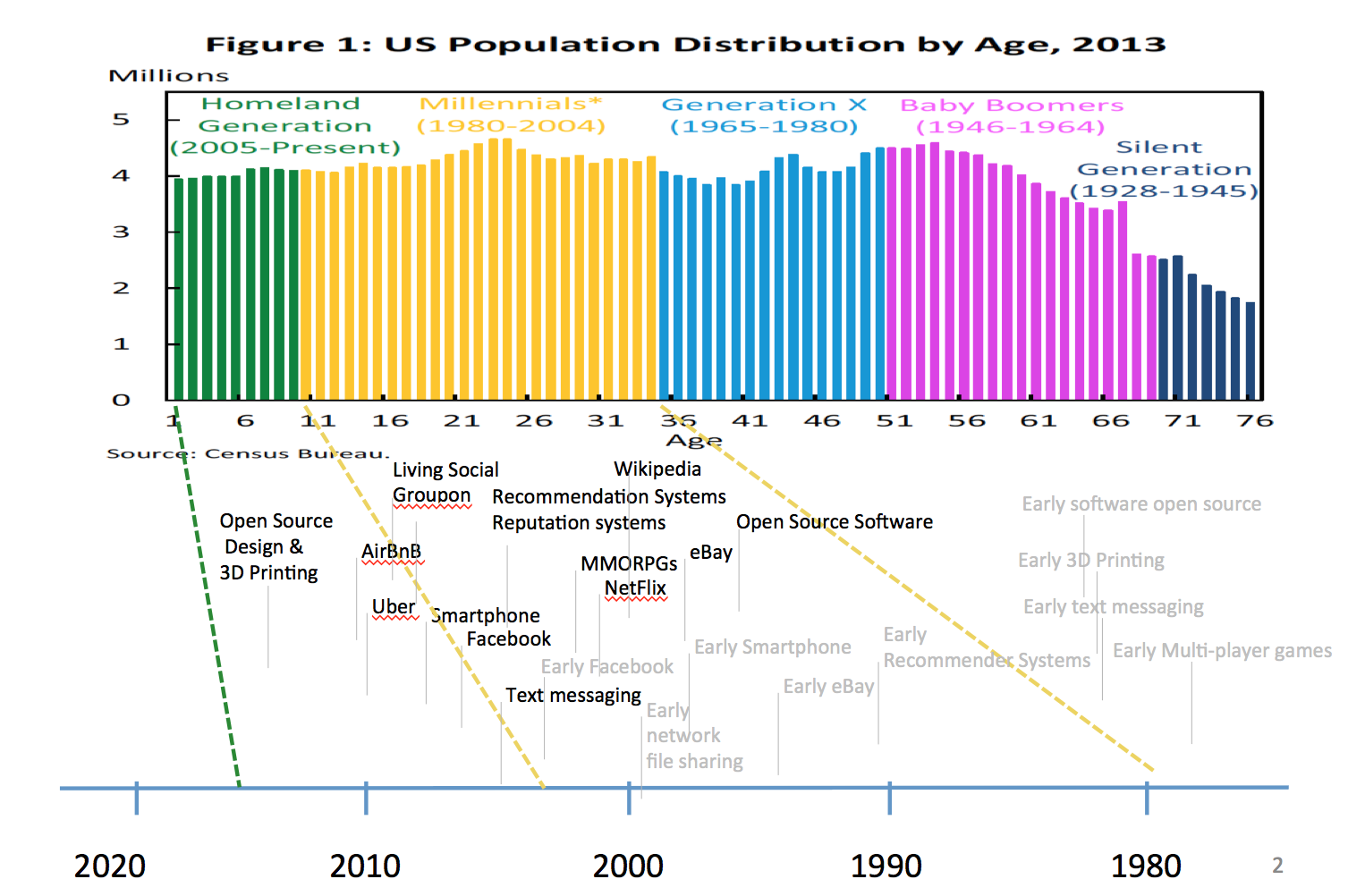

For some of us, the idea of having computers on the team is outside of normal experience. However, for Millennials, human-computer teaming is the natural next step in a way of life that they have grown up with since they started arriving in 1980. The graphic shows how the technology elements of human-computer teams came into regular use as Millennials grew up.

For example, Wikipedia arrived in the early years of the first Millennials. It is now the most popular encyclopedia by far. The computer role in Wikipedia is mainly about tracking changes, managing editorial workflow and spotting spamming. However, combined with the human cognition that drives editorial decisions, Wikipedia has now ranked among the top five or ten Internet sites for decades.

The Wikipedia example illustrates a major cultural shift in how Millennials communicate. Computers intermediate most of their communications. Other examples include text messaging, which began in the early 2000’s and took off with smartphones in about 2007. Facebook and other social networks take computer-intermediated communications to new levels – greatly outpacing older technologies like email as more enhanced ways of communication intermediated by computers.

Today the “agent” on the other end of the message or chat may be a messenger bot. “Messaging as a platform” is fueling a new round of start-up funding for services where people make requests from computers via texting or chat programs. Apple’s Siri and Amazon’s Echo are two well-known examples where “your wish is my command” in computer-intermediated services.

How do you get advice today? Computer-intermediated recommendation systems started appearing in the early 2000’s to gather and dispense our collective advice for finding good restaurants and services using Yelp, Angie’s List and many others. Systems that recommend books and movies routinely use computers to hone the relevance of recommendations by modeling our own preferences.

Millennials grew up with computer-intermediated coordination. This is central in multi-player and massively multi-player games (MMORPH), which are now a multi-billion dollar industry. But other computer-coordinated activities include eBay (late 1990’s) for coordinating auctions.

Computers that enable the sharing economy emerged in about 2010 with computer-intermediated coordination enabling people to share rides on Uber, book homes or rooms on AirBnB, and so on. Millennials were the founders and early adopters for these computer-intermediated ways of working and living.

In summary, our world is increasingly computer-intermediated, computer-coordinated, and informed by computer cognition. Human-computer teams are next.

What any of us consider “normal” depends on what we grew up with. For Millennials, these directions are not surprising. Their question is not whether the future of work is human-computer teams. It may be more like, “what’s taking it so long?”

My group at PARC is called TAO, which stands for Theory and Technology for Agile Organizations. We design and implement web services that help organizations optimize their activities, using mobile and cloud technology. Thanks to the CitySight team and our partners for all of the discussions and design that informed this project. Thank you to Matt Darst, Hoda Eldardiry, Bob Krivacic, Lawrence Lee, Raj Minhas, Sai Nelaturi, Mudita Singhal, and Barbara Stefik for comments on earlier versions of this post.

The typical news today about LED bulbs is about their rapid adoption, their dropping prices, and supporting legislation. The bigger story is about exploiting the IOT (Internet of Things) infrastructure that surrounds them.

Lightbulbs have great established infrastructure. Each receptacle is wired for power. Bulbs have standard screw bases for simple bulb installation.

Lightbulbs have great established infrastructure. Each receptacle is wired for power. Bulbs have standard screw bases for simple bulb installation.

Light bulbs are everywhere. The average American home has about 40 receptacles for light bulbs. By various estimates there are between 2 billion and 4 billion light bulbs installed in the U.S. That number represents an eighth of the world market.

Traditional incandescent bulbs have a simple function. They glow when they are supplied with power. Manufacturers of LED bulbs are already adding functionality, mostly copying or extending what traditional bulbs do. There are LED bulbs that can dim, ones that can change color, and so on. They can be controlled from a phone or computer via WIFI.

“Smart bulbs” cost more, but they save energy and last longer. A typical LED bulb used three hours per day should last 20 years or more. This long expected product life changes our perception of a bulb from a short-lived disposable to a pricier but long-lived appliance.

What could be incorporated in a light bulb?

How could that work if the power to the bulb is off? Suppose that power to a bulb is generally left on but the bulb has a smart circuit that turns the glow on or off. A bulb could glow depending on any number of factors including darkness, detected motion, time of day, sound and commands sent via the WIFI.

Bulbs could have batteries so that they can still perform some actions when their power is off for an extended time, such as emergency lighting or communicating a message through a WIFI. They could trickle charge the battery and run computations without glowing.

Staying close to conventional bulb functionality, lights could adjust brightness according to need. Just say “More light” if you want more brightness and “Lights out” if you want darkness, and so on.

You could even give simple commands through a light switch. Flick the switch twice to turn the glow on. Flick it once to turn glow off. Flick it three times to go to a brightness adjusting mode where each additional flick brightens the glow a little.

You could even give simple commands through a light switch. Flick the switch twice to turn the glow on. Flick it once to turn glow off. Flick it three times to go to a brightness adjusting mode where each additional flick brightens the glow a little.

How else can we go beyond familiar lighting functions?

So, what is the right operating system for a light bulb? That answer will change with time, but these examples of applications suggest that there is value in supporting multi-processing and other familiar capabilities for embedded systems. Viewed this way, light bulb systems should be developed as a standard part of a system of systems.

What other IOT devices would be useful in light bulb sockets?

Thanks to Eric Bier, Danny Bobrow, Kyle Dent, Raj Minhas, Ashwin Ram, Frank Torres, Michael Youngblood, and Ed Wu for earlier conversations on this. Thanks to Barbara Stefik for providing pictures while I was spending time at the airport writing this.

In Edinburgh they call them “closes”. Other names include arcades, lanes, and alleys. For urban designer Christopher Alexander, an alley is kind of pedestrian street (design pattern #100). A shopping alley is an alley with store fronts. It is often an integral part of a shopping street (pattern #32).

How do shopping alleys work and what can they teach us about designing apps for exploring neighborhoods in smart cities?

Shopping streets are the hearts of urban neighborhoods. People walk from store to store and enjoy the atmosphere at sidewalk cafes. The attractiveness and safety of these areas is enhanced when pedestrian traffic is separated from vehicle traffic.

Christopher Alexander characterizes pedestrian streets as essential for public life. As he puts it:

“The simple social intercourse created when people rub shoulders in public is one of the most essential kinds of social “glue” in society.” — from A Pattern Language

When a shopping street is well designed, it becomes a magnet, attracting commerce and people from other neighborhoods in a city.

In contrast to well-developed shopping streets, undeveloped alleys can be dangerous and dirty places filled with garbage cans and populated by derelicts. How can well-designed shopping alleys improve livability and shopping streets?

Shopping streets tend to grow at their ends. The Champs-Élysées is an extreme example, stretching over a mile in northwestern Paris from the Arc de Triomphe to The Place de la Concorde near the Louvre. As shopping streets stretch out, the average distance between two stores on the street increases and the street loses its sense of being a compact place to walk and shop.

[pullquote]As shopping streets stretch out, the average distance between stores increases and the sense of a compact area for shopping is diminished.[/pullquote]The main street is the prime real estate and focus of foot traffic. When shopping streets extend sideways to adjacent streets to become shopping districts, there is typically a large drop in foot traffic compared to the main street.

We can model shopper behavior using optimal foraging theory. Arising from research in ecology, the theory says that organisms forage in a way that maximizes their net energy intake in each unit of time. To model shoppers in this way, we assume that shoppers will seek areas with the most opportunities for buying attractive goods and services in each unit of time.

Human shopping behavior has much in common with ancestral patterns for hunting and gathering. As a thought experiment, imagine an early human heading off to a berry patch to gather food. The patch is an attractive destination since much food can be gathered in a short time. Suppose that on the path back from the patch there is a walnut tree. A quick side trip enables harvesting additional food.

[pullquote]A well-designed shopping alley enhances foraging by bringing many small shops into view from a shopping street.[/pullquote]Insights about shopping streets from foraging theory address two points of view. One view is that of the optimizing shopper who goes directly to a destination for a particular item, and also who prefers shopping in a “rich patch” in order to pick up a few things. The second view is that of the shop keeper, who wants to design a place that attracts shoppers. Because the total traffic is the sum of shoppers who come for specific things (the “berries”) and those who are attracted by something they see while foraging (the “walnuts”), shop keepers find an advantage in having their shop be in a rich patch for foraging. To optimize business, they need foot traffic and a means to attract people walking by.

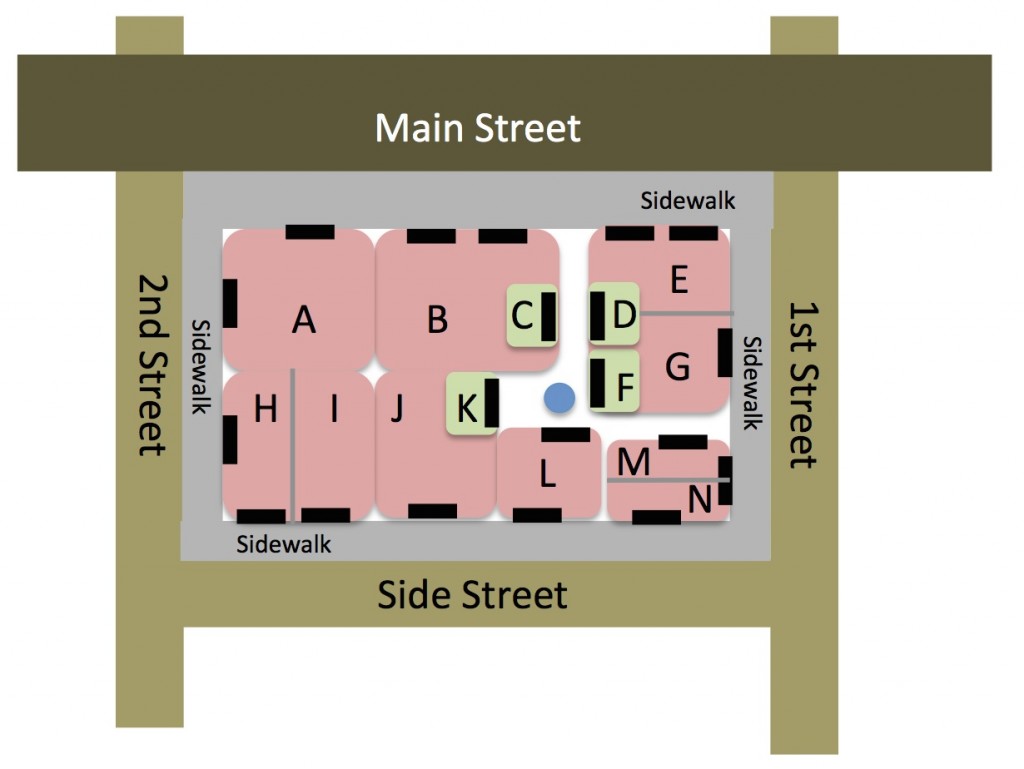

The alley (in white) can bring small stores C, D, and F within view and easy walking distance for shoppers on Main Street.

Consider how a developed shopping alley brings a variety of small shops into view from a main street. In the figure above, walkers who stay on Main Street would go by stores A, B, and E in order. The shopping alley (shown in white) brings stores C, D, and F within ready view and easy walking distance. It invites us to explore them. Exploring a shopping alley is much easier than walking around the block to more remote stores. Stores C and D off Main Street are more visible and visited than stores H, I, J, L, M, and N on the cross streets or side streets.

Because they invite exploration of many options in a short time, shopping alleys provide a richer foraging experience than a simple main street.

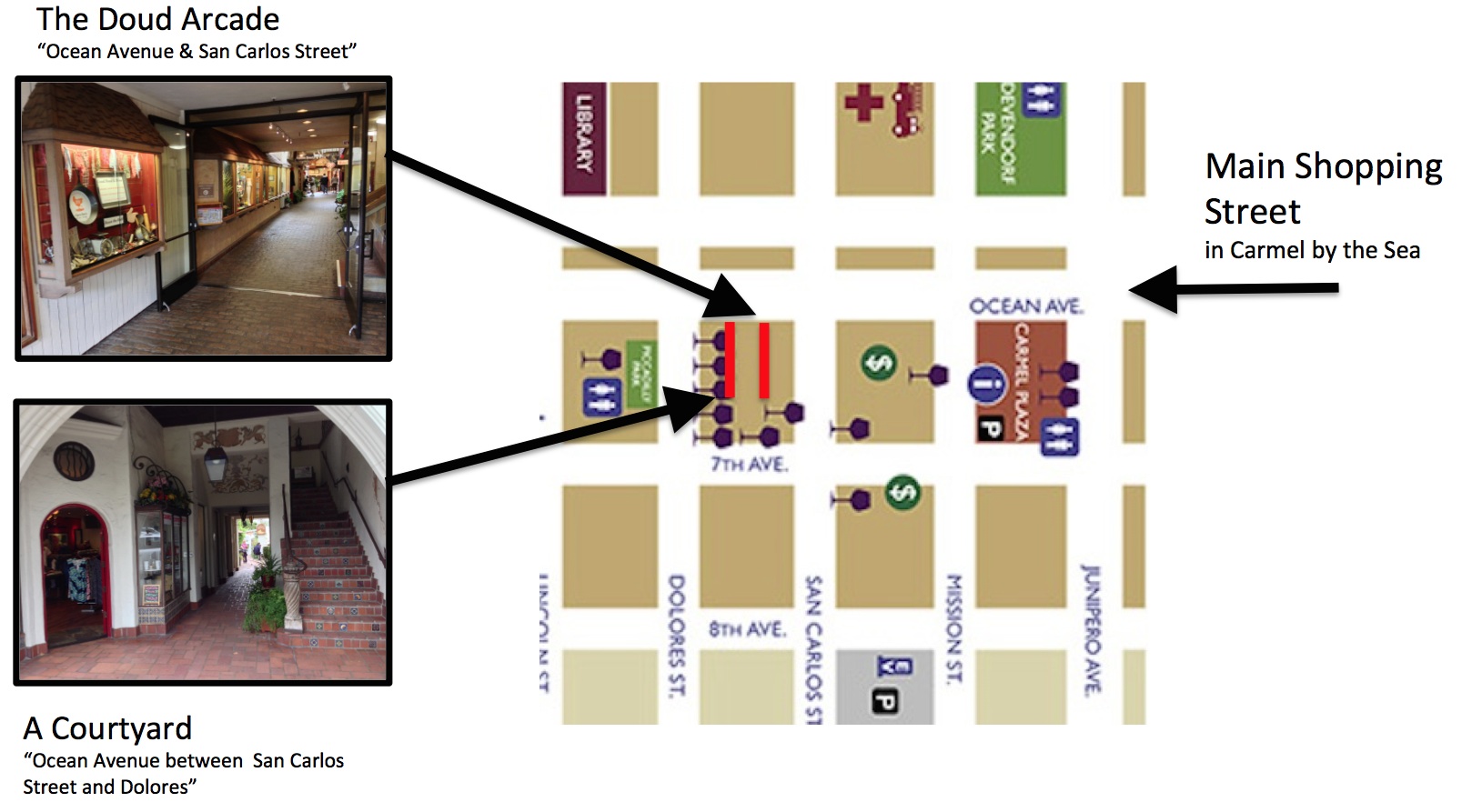

[pullquote]A shopping alley increases the density of attractive shops and improves the foraging experience.[/pullquote]A shopping alley provides a rich opportunity for foraging. Consider the Doud Arcade in Carmel, California shown in the first photo above. The arcade opens off Ocean Avenue, which is the main shopping street in Carmel. The arcade has skylights. Lighted displays of goods and store windows on the alley’s exterior walls attract people to alley stores. Compare this photo to the undeveloped alley above in Palo Alto, California, where shoppers walk quickly by hurrying to the next interesting offering on the street.

As a tourist destination in California, Carmel has developed Ocean Avenue to enhance the town’s appeal. The diagram above shows both Doud Arcade and a courtyard on the same block. The restaurants and stores on these shopping alleys are more accessible for foraging than stores on 7th Avenue which is the next street over.

As a tourist destination in California, Carmel has developed Ocean Avenue to enhance the town’s appeal. The diagram above shows both Doud Arcade and a courtyard on the same block. The restaurants and stores on these shopping alleys are more accessible for foraging than stores on 7th Avenue which is the next street over.

El Paseo (meaning “The Walk”) in Sonoma, California, is a shopping alley off the main square shopping street. Like the Doud Arcade in Carmel, the entrance has signs and decorations intended to attract walkers to explore as they encounter it on the main street.

The Old Town of Edinburgh, Scotland, is the oldest part of Scotland’s capital city. The Royal Mile is the main artery and shopping street that runs down from Edinburgh Castle. Many small alleyways — courts, entries, and wynds branch off the road. These are generically called closes. Some of them lead to museums, stores, restaurants and other points of interest. Closes tend to be narrow, although many of them open up to courtyards. Paisley Close shown on the left leads to a Celtic Craft Centre.

Alleys in many towns are a carry over from earlier times when they were used for deliveries and trash pickup. In Mountain View, California and the California Avenue area of Palo Alto (originally the town of Mayfield), alleys lead to parking lots a block off the main street. In such areas the potential of alleys is just being recognized. Development as shopping alleys would require remodeling underused sections of buildings in order to provide space for small shops.

The elements of “bad alleys” are well known. They may be dirty and unpaved. They may have garbage cans. Beyond the obvious cosmetics, successful shopping alleys are arranged so that people on the main street can see at a glance what they have to offer. At a minimum they have signage about the stores or restaurants. Beyond that they may have windows into the stores or lighted displays of goods available down the alley. In the main, the successful shopping alleys enrich the forage experience of walkers by giving them an easy way to get a sense of what is available on a short side trip.

[pullquote]Many cities are developing all kinds of alleys to improve urban livability.[/pullquote]Seattle, Chicago, Palo Alto and many other cities are re-developing all kinds of alleys to bring vitality to their neighborhoods and to improve urban livability. As in the Palo Alto photo on the left, downtown alleys and new construction have been combined to create public areas that are now a vibrant part of the night life.

In Seattle, the Alley Network Project is working with neighbors, businesses and community groups to revitalize alleys. They studied how neighborhoods in the U.S. and abroad have revitalized their alleys. A group at the University of Washington Green Futures Lab developed The Seattle Integrated Alley Handbook: Activating Alleys for a Lively City to help people re-imagine their alleys and make them lively, healthy, safe and environmentally friendly.

In San Francisco, The Linden Living Alley offers a book that describes design patterns for alleys. They have found that revitalized alleys not only improve shopping and livability, but they can also provide spaces for incubating cottage industries. The Downtown Denver Partnership is making plans to revitalize alleys along Denver’s famous 16th Street Mall. In Chicago, the Green Alley Handbook documents the city’s plans for managing alleys, handling waste water and heat issues, and generally making neighborhoods in the city more livable. In New York, the Voices celebrates the alley with a back street history of New York communities.

Even though alleys are so small, the principles behind their design patterns can inform design for smart cities.

Alley renewal projects recognize and make use of existing city resources. In the same way, although there is much news about experimental smart cities and the trend toward mega-cities, most projects for smart cities in the next decades will be retrofitting and renewal. We are challenged to recognize the resources already present and to incorporate them into a vision of renewal.

As Christopher Alexander put it, shopping streets and other pedestrian ways provide a setting for much of our social glue. The enjoyment that people experience in these areas contributes to a sense of livability for neighborhoods. As in the photo from the Spanish Steps in Rome, people go to shopping streets to see and be seen. When we are on a shopping street, we see friends, we see what people are doing, how busy it is, whether the restaurants and shops are open, and so on.

Consider the two adjacent cities Palo Alto and Menlo Park on the San Francisco peninsula. In the evening, Palo Alto is alive with coffee shops and restaurants. People walk about in groups and couples. They pitch deals and discuss business over laptops everywhere at tables on the sidewalk at coffee houses and restaurants along University Avenue. Although Santa Cruz Avenue in Menlo Park has a number of stores and restaurants, except near El Camino Real it is much quieter on most nights. As a friend quipped, “They roll up the sidewalks in Menlo Park”.

[pullquote]Increasingly we use apps as our lenses for seeing things at the scale of cities. But there are too many of them and they do not convey a sense of place.[/pullquote]Other than by going there, if you did not know the peninsula and were looking for a place to dine or shop, how could you anticipate this difference between the cities? Increasingly we use the virtual world and social media as lenses for seeing things at the scale of cities.

There are dozens of apps for cities in many urban centers. There are apps for finding parking, apps for finding restaurants and making reservations, apps and web pages for finding out about stores, apps to guide travel by car, bus, or bike, apps for local news, apps for community participation, and so on. But that’s actually the problem. Such a pile of apps does not convey a sense of place.

[pullquote]At the scale of cities, an app should support foraging at the next level — finding attractive neighborhoods[/pullquote].Looking at patterns of well-designed shopping alleys provides some design hints. Shopping alleys make it easy to get an overview. They invite us to explore. At the scale of cities, an app should support foraging at the next level — finding attractive neighborhoods. It needs an intuitive interface that tells us about the following:

Top designers of apps and web pages bring an understanding of information foraging theory to their designs. The theory says that people rely on “information scent” or context of nearby information to help them navigate and choose which links to click. The design challenge is to create an app for exploring information about smart cities that is as easy and efficient as walking on a shopping street. Such an app would encourage people to explore their city like they explore their neighborhoods.

[pullquote] The design challenge is to provide foraging and social experiences at city scale as natural as walking on a shopping street and exploring its shopping alleys.[/pullquote]Many people point to European cities built before cars became prevalent as favorite places for pedestrians. As one of its customers said about Cafe Borrone’s in Menlo Park, you go there “because Europe is too far to go for lunch”. As a German colleague told me:

“Coming from Germany, I’ve always missed the pedestrian zone in German cities. They serve as the face of the city. You go there to see and be seen. Shops may or may not even matter that much. In some sense they just provide the (productive) excuse for everyone to go. Once you are there, you pay as much attention to other people as you do to the shops themselves. It’s the atmosphere that matters and vitalizes, especially on those first warm days in the spring when everyone is just smiling.” — Christian Fritz

[pullquote]We can use foraging theory to guide design of shopping alleys and apps, helping us to easily find places we love to go.[/pullquote]By following design principles that acknowledge foraging behaviors, we can revitalize cities with shopping alleys and apps. Optimal foraging theory challenges us to revitalize shopping streets with shopping alleys and public spaces. In a similar way, information foraging theory challenges us to create fresh designs for apps that invite us to explore and enjoy our cities beyond our familiar neighborhoods. There are already apps in many cities that tell us how to get there (driving, walking, or multi-modal). The challenge is to design apps as lenses that help us to optimize our time and easily find places we love to go.

This post was written by Mark Stefik and Barbara Stefik. Thanks to Leonid Antsfield, Dan Bobrow, David Cummins, Christian Fritz, Melissa Hart, Lawrence Lee and Ed Wu for comments and suggestions on earlier drafts.

It is counterintuitive, but as Wired says, building more roads increases traffic. How can we do better?

On a wall at Xerox Services in Los Angeles there is a photo of Sepulveda Grade packed with cars from the 1950’s and 1960’s. As a colleague observed the highway is now widened and includes high occupancy (diamond) lanes. But it is just as crowded and congested as before. Researchers, like Giles Duranton and Mathew Turner, study and quantify the relationships between highways and miles driven, modeling demand and weighing different influences.

On a wall at Xerox Services in Los Angeles there is a photo of Sepulveda Grade packed with cars from the 1950’s and 1960’s. As a colleague observed the highway is now widened and includes high occupancy (diamond) lanes. But it is just as crowded and congested as before. Researchers, like Giles Duranton and Mathew Turner, study and quantify the relationships between highways and miles driven, modeling demand and weighing different influences.

We wanted to find a simple way to understand this phenomenon. Crowded highways exemplify how our collective will and intuitions for urban projects can lead to unexpected consequences and failures. The collapse of some exburbs into slums may be another example at the larger scale of cities connecting to surrounding cities. These examples are leading us to reflect on how we could do better in designing smarter, more sustainable urban systems.

We are struck by the visual similarity of city overviews to circuit boards and chip layouts. With a little imagination, integrated circuit chips and other components look a bit like buildings and other structures. Printed connections suggest streets and carry “traffic” in the form of electrons or information from one place to another.

Although the analogy can be useful, the main point is that reasoning about “traffic” requires systems thinking. In both cases designers wrestle with trade-offs in function and connectivity. They design subsystems at multiple levels. For cities, there are rooms, buildings with multiple stories, neighborhoods, main cities, satellite and surrounding cities, and networks of cities connected by highways, trains, and such. For electronic systems we have printed components on a chip, chips on boards, boards in back planes, computers on local area networks, and systems and services connected over the web. These systems-level design and coordination issues arise in all distributed control systems.

Although the analogy can be useful, the main point is that reasoning about “traffic” requires systems thinking. In both cases designers wrestle with trade-offs in function and connectivity. They design subsystems at multiple levels. For cities, there are rooms, buildings with multiple stories, neighborhoods, main cities, satellite and surrounding cities, and networks of cities connected by highways, trains, and such. For electronic systems we have printed components on a chip, chips on boards, boards in back planes, computers on local area networks, and systems and services connected over the web. These systems-level design and coordination issues arise in all distributed control systems.

[pullquote]You can increase bandwidth between subsystems with more and faster connections. But to understand traffic flow, you need to understand what governs people’s behavior.[/pullquote] Successful design in both areas requires the ability to understand how subsystems interact. For example, it is important to distinguish tightly-connected and loosely-connected subsystems at all levels. To increase the maximum traffic or bandwidth between subsystems and reduce turn taking and waiting at rush times, use more or faster connections. However, connections can also make things worse. When systems are connected, activity in one area affects activity and traffic in other areas. Consequently, bottlenecks and congestion can arise.

To understand performance in computing systems designers need to understand load balancing and demand models for programmed systems. To understand the system effects and traffic for cities, designers need to understand what governs human travel behavior.

Consciously or not, people have time budgets for travel. The profile of commuters in the U.S. is multi-modal with long and short commutes, but on average Americans travel about 25 minutes each way to work. Besides commuting, people travel at different times of the day for various purposes. The average American day includes not just work, but also entertainment, household activities, shopping, and so on. Each of us decides where and when to travel. Figuring it out is complex. Do we count waiting in line? Walking kids to school? We make choices about travel all day long.

[pullquote]The choices we make are limited by the options available in our environment. [/pullquote]Consider Adam and Betty who live in a city neighborhood. They have a car but also use public transportation. They try to shop wisely, but the costs and varieties of things in their neighborhood stores are limiting. They sometimes go to distant stores, but they are not willing to travel for hours just to shop. When there are good choices for traveling long distances quickly, they are more likely to use them. In a nutshell, this story shows why faster roads and other forms of transportation increase traffic. People travel more when fast connections increase their living options.

[pullquote]People choose places that offer good life choices.[/pullquote]The typical workday traffic pattern is shaped by answers to two questions: Where do you work? And where do you live? Our choices are limited by the options available in our environment. We pick places that offer good life choices.

Commute time is only one factor when people make decisions about where to live. Some people want to spend more time commuting in order to live in a place that provides a better quality of life such as bigger living space, a better school district or other important aspects.

In the 1950’s suburbs started to grow rapidly. World War II had ended and a generation wanted to seize life with a dream of a home in the suburbs. Enabled by cars, cheap gasoline, and investment in highways, suburbs grew all over the country. Half a century later, that approach is breaking down. Energy prices are up and the best paying jobs are in the cities. With their economic efficiencies, cities are offering better choices for new generations. On a global scale people are moving out of the country and into cities and mega-cities. Can we evolve our cities to provide better and more sustainable options for living?

Christopher Alexander was an architect who became well-known in part because of his foundational work on design patterns. Design patterns are good design examples of subsystems, complete with descriptions of where they apply. Alexander paid close attention to how people lived and used spaces in their homes and cities. With his colleagues, he set out to help others create livable designs by providing a book of tested design examples. The idea was to start with the patterns and to adopt and combine them in the design of larger systems. Since then the idea of design patterns has successfully spread to the design of software, computer systems, and distributed control systems among others.

Christopher Alexander was an architect who became well-known in part because of his foundational work on design patterns. Design patterns are good design examples of subsystems, complete with descriptions of where they apply. Alexander paid close attention to how people lived and used spaces in their homes and cities. With his colleagues, he set out to help others create livable designs by providing a book of tested design examples. The idea was to start with the patterns and to adopt and combine them in the design of larger systems. Since then the idea of design patterns has successfully spread to the design of software, computer systems, and distributed control systems among others.

[pullquote]We need urban system design patterns that show where they apply, what their limitations are, and how new technology is changing the rules. [/pullquote] Today new technologies are enabling new design options for cities. Sensors, big data, modeling and analytics are helping to manage shared resources by sensing the environment and providing smart incentives to influence behavior. An example is the use of congestion pricing in London and Singapore. Another example is the use of dynamic pricing for parking in Los Angeles and San Francisco. Cities like Munich turn streets into pedestrian-only shopping areas during midday hours. Cities like London and Portland, Oregon have renewed their waterfront areas to provide people-friendly areas for walking and accessing shopping. Cities like Paris and experimental smart cities like Masdar near Abu Dhabi are paying attention to classical examples of neighborhoods with narrow streets designed for people rather than cars. These are examples of successful patterns. We need more design patterns that show where they apply, what their limitations are, and how they integrate with new technology. Interest is now growing in urban planning and systems designers in creating design patterns for smart cities.

[pullquote]We need urban system design patterns that show where they apply, what their limitations are, and how new technology is changing the rules. [/pullquote] Today new technologies are enabling new design options for cities. Sensors, big data, modeling and analytics are helping to manage shared resources by sensing the environment and providing smart incentives to influence behavior. An example is the use of congestion pricing in London and Singapore. Another example is the use of dynamic pricing for parking in Los Angeles and San Francisco. Cities like Munich turn streets into pedestrian-only shopping areas during midday hours. Cities like London and Portland, Oregon have renewed their waterfront areas to provide people-friendly areas for walking and accessing shopping. Cities like Paris and experimental smart cities like Masdar near Abu Dhabi are paying attention to classical examples of neighborhoods with narrow streets designed for people rather than cars. These are examples of successful patterns. We need more design patterns that show where they apply, what their limitations are, and how they integrate with new technology. Interest is now growing in urban planning and systems designers in creating design patterns for smart cities.

What are the design patterns for neighborhoods that provide people with better options for life choices without needing to travel as much? What are design patterns at the city level and at the “system of cities” level? What design patterns enable easy travel of people without competition with delivery of goods? What are examples of patterns for time-shifting some activities to lower contention and congestion? What are design patterns for reserving use of scarce resources such as loading zones, parking spaces, or very fast travel connections?

What are the design patterns for neighborhoods that provide people with better options for life choices without needing to travel as much? What are design patterns at the city level and at the “system of cities” level? What design patterns enable easy travel of people without competition with delivery of goods? What are examples of patterns for time-shifting some activities to lower contention and congestion? What are design patterns for reserving use of scarce resources such as loading zones, parking spaces, or very fast travel connections?

The urban situation keeps changing. The millenials are adopting to cities, are less likely to have personal cars, and are choosing smaller vehicles. Virtual offices and telecommuting may be on the rise. People are doing more internet shopping with delivery. As things evolve, what other questions should we be asking?

The first underground railways were built in the 1860’s in London. Subways systems increase living options for city dwellers by enabling rapid travel between city neighborhoods while avoiding surface-level congestion and without spreading out the city with surface-level parking facilities. An analogous pattern arises in circuit design with multiple layers of connections in three dimensional chips and also in multi-layer printed circuit boards.

[pullquote]We are looking for tested and inspired patterns at all scales, especially with models that can give quantitative economic and livability indicators.[/pullquote] We find it intruiging that computing technology is not only enabling new options for cities, but that the analogous design problems for computer systems encourage systems thinking and may provide inspiration for new urban patterns. We need patterns at the scale of neighborhoods and also at the scale of urban regions.

This post was written by Mark Stefik, Pai Liu, and Hoda Eldardiry. Thanks to David Cummins, Ken Mihalov, Craig Heberer, Bob Ruybal, Melissa Hart, Walt Johnson, and Barbara Stefik for comments on earlier drafts.

When edge cases become typical they signal transitions. Then we need new thinking for real understanding.

When edge cases become typical they signal transitions. Then we need new thinking for real understanding.

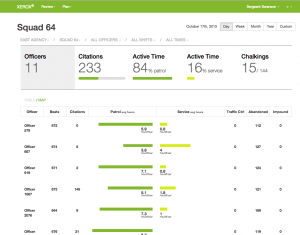

Edge cases are usually rare and far from the norm. They can challenge and inform how we think. They come up in answering even simple seeming questions on our project, which is developing analytics for traffic and parking enforcement organizations.

Parking enforcement takes place in the context of managing urban transportation. Depending on the city, enforcement organizations can be in a Department of Transportation, a Department of Public Works, or a police department. Sometimes other departments in a city are involved in handling city garages or public parks.

Parking enforcement takes place in the context of managing urban transportation. Depending on the city, enforcement organizations can be in a Department of Transportation, a Department of Public Works, or a police department. Sometimes other departments in a city are involved in handling city garages or public parks.

Enforcement organizations manage their activities in terms of shifts and beats. As in other jobs, shifts represent the hours that people work. Beats correspond to geographic areas in a city. The idea of “walking a beat” is traditional. Besides walking beats, there are also beats where officers use cars, carts, bicycles, Segways, and other kinds of vehicles.

Enforcement organizations manage their activities in terms of shifts and beats. As in other jobs, shifts represent the hours that people work. Beats correspond to geographic areas in a city. The idea of “walking a beat” is traditional. Besides walking beats, there are also beats where officers use cars, carts, bicycles, Segways, and other kinds of vehicles.

An officer is assigned a beat on his shift. Squads or teams of officers are managed by supervisors (sometimes called sergeants), and groups of sergeants report up to their managers (sometimes called captains). In one city we work with, officers are called “technicians.” Increasingly city departments are expected to be efficient. Data-driven enforcement is part of the movement to develop “smarter cities”.

Consider a conversation between a supervisor and an officer, relayed to us during fieldwork (details changed).

Sergeant: It looks like you got a string of tickets in beat #14 yesterday. Officer Jones is complaining about poaching.

Officer Smith: Oh, right. I was returning from a traffic control assignment on Main Street. Did you want me to just drive by cars that were double-parked and cars parked in the bus zone (contrary to department policy)?

This conversation took place in a city where enforcement officers fulfill many responsibilities. These include traffic control when there is an accident, a fire, or a power line down in a storm. Officers may also supervise traffic at schools during busy periods when parents are dropping off or are picking up kids. Such activities are broadly characterized as “service” activities and are part of the public safety mission of the departments.

This conversation took place in a city where enforcement officers fulfill many responsibilities. These include traffic control when there is an accident, a fire, or a power line down in a storm. Officers may also supervise traffic at schools during busy periods when parents are dropping off or are picking up kids. Such activities are broadly characterized as “service” activities and are part of the public safety mission of the departments.

In order to respond to service needs, enforcement organizations have dispatchers that can re-deploy nearby officers. When officers travel to and from service assignments, they sometimes pick up citations along the way. In the conversation above, Officer Jones complained that in working his beat he came across a block where the citations were already picked up — wasting his time and potentially hurting how his supervisor will see his performance.

[pullquote]In optimal foraging theory, hunters want others to stay out of their territories. They will collaborate only if there is an incentive.[/pullquote]The idea of “beats” reflects a way of thinking where a department divides a city into areas of a size that an officer can cover in a shift. Each officer is responsible for his own beat. This approach has several advantages. It is easy to describe. It spreads officers out so that they stay out of each other’s way. It does not require much ongoing communication. In analogy with optimal foraging theory, officers are analogous to hunters and beats correspond to hunting territories. Hunters want others to stay out of their territories. In foraging theory, hunters will collaborate if there is an adequate incentive, such as catching more game.

Beats were used to organize enforcement long before wireless communication systems were available. The deployment of Officer Smith to handle the traffic control responsibility departs from the simple beat approach because it interrupts his activity. Wireless communication enables organizations to respond more quickly to events and to assign officers dynamically where they are most needed. The example shows how organizations are evolving. Organizations now operate in a dynamic world, where communication enables information to flow quickly. Organizations are expected to respond and adapt. They now operate with multiple, competing goals in overlapping time frames.

Although working with agility is complex, embracing it ultimately leads to a deeper understanding and higher performance. A transition to agility can be supported by better analytics.

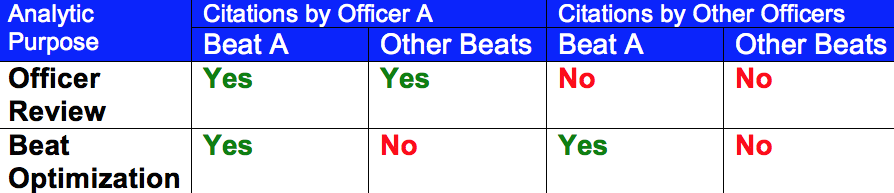

Edge cases require little when they are rare. In a study of citations for one of our clients, however, we found that over 60% of the citations issued on some beats were given by officers other than the one assigned. In that city, the interference between officer activities is no longer an edge case, but is becoming the norm. When that happens, thinking about how the organization works using just the traditional mindset of beats and shifts becomes an obstacle to operations and performance optimization. Consider the following question addressed in typical citation analytics:

“How many citations did Officer A issue on his shift?”

The proper answer depends on the question’s purpose.

The proper answer depends on the question’s purpose.

Suppose a supervisor wants to review the performance of Officer A on his beat. She wants compare his performance to the previous performance of other officers on that beat during the same shift and day of the week in the same season. Should a citation count include tickets issued by the officer on other beats as he traveled to and from service assignments? If the day was typical and the service assignments were typical, the supervisor probably wants to consider his performance for the entire activity. Should tickets on the officer’s beat made by other officers traveling through be included? Probably not. On the other hand, if a manager wants to understand compliance on a beat, then tickets by anyone should be counted and off-beat tickets by the assigned officer should not.

These two analytics options are just a beginning. Situations have nuances. How much time did the officer spend on his own beat versus others? Did the officer pass through other beats with much richer or poorer prospects for “hunting” citations? Did the officer pick up most of his citations at the end of the shift? We are developing spatial and temporal dashboards that can convey much richer stories about a “day in the life of an officer”, and also dashboards that convey explanations very simply. It is important to have multiple views of the data to illuminate what the constraints are, and our options in addressing them.

[pullquote]Recipe for coordination: better analytics, incentives, communication, and context awareness.[/pullquote] In analytics design, framing the right questions requires understanding organizational goals. When organizations adopt more agile approaches than traditional shifts and beats, they are trying not only to increase agility but also to optimize team performance. Increasing team performance requires increased coordination and collaboration. Increased coordination requires incentives, effective communication and context awareness for team members.

Thinking back to the example conversation where Officer Jones complained about Officer Smith “poaching,” a significant part of the issue was that Officer Jones did not know that the block was already covered. If Officer Jones’ mobile device kept him peripherally aware of Officer Smith’s activities, he need not have traveled to that block.

How else might a squad coordinate and collaborate? How could teamwork be more like players on a team sport passing a ball to set up scoring a goal?

Ideas about organizational culture and design questions are at the leading edge of thinking about optimizing team performance. Always under pressure to be efficient, enforcement organizations are also under pressure to be agile. They are often in transition to new ways of thinking. They need policies to set priorities and incentives, better analytics to help them understand and plan their policies and their dynamic activities, and ways to support coordination and collaboration.

(Thanks to Dan Bobrow, Eduardo Cardenas, David Cummins, Melissa Hart, and Ken Mihalov, and Farrukh Ali for comments on earlier versions).