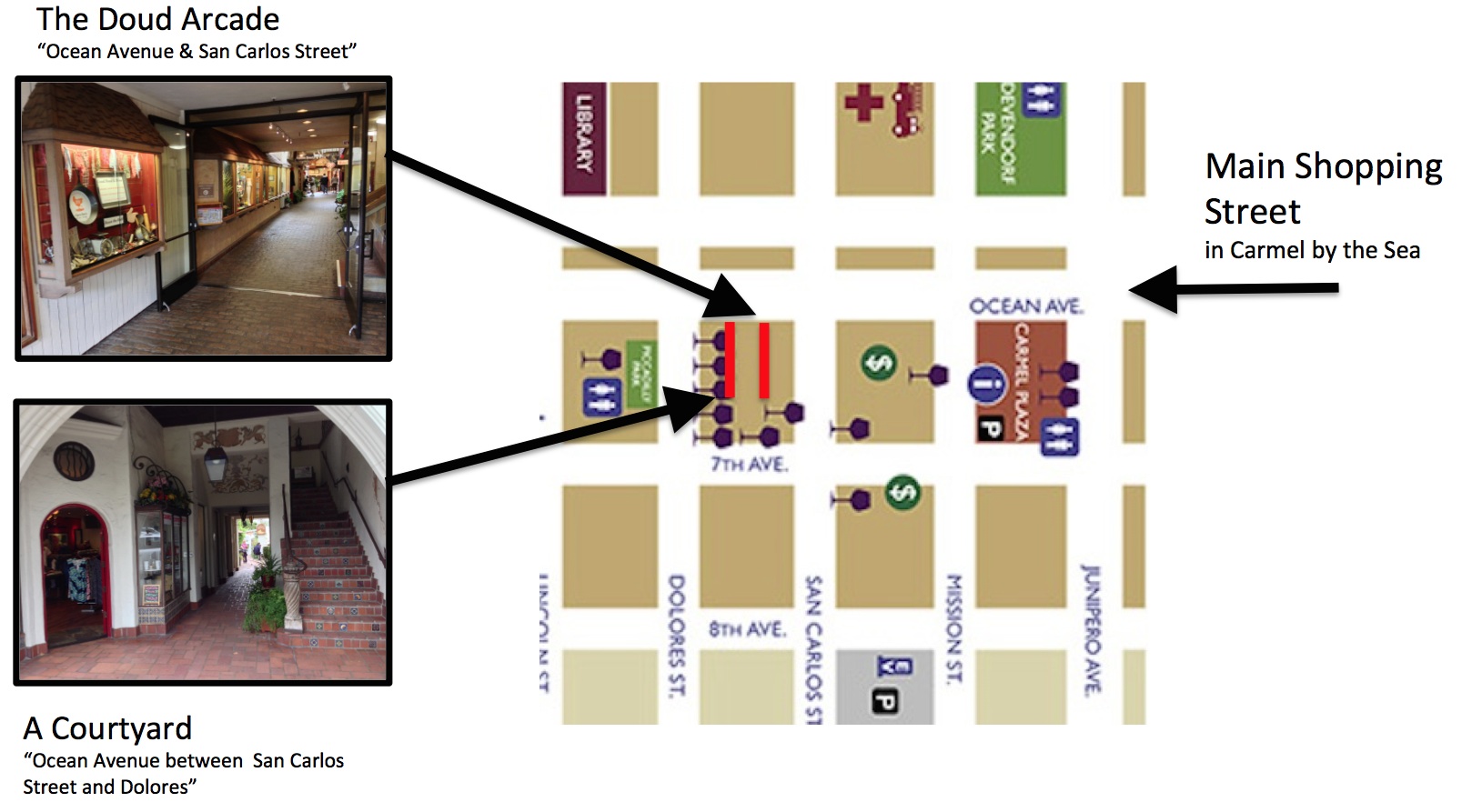

Doud Arcade off Ocean Avenue (Carmel, CA.)

In Edinburgh they call them “closes”. Other names include arcades, lanes, and alleys. For urban designer Christopher Alexander, an alley is kind of pedestrian street (design pattern #100). A shopping alley is an alley with store fronts. It is often an integral part of a shopping street (pattern #32).

How do shopping alleys work and what can they teach us about designing apps for exploring neighborhoods in smart cities?

Shopping Streets

Shopping Street in Paris, France.

Shopping streets are the hearts of urban neighborhoods. People walk from store to store and enjoy the atmosphere at sidewalk cafes. The attractiveness and safety of these areas is enhanced when pedestrian traffic is separated from vehicle traffic.

Christopher Alexander characterizes pedestrian streets as essential for public life. As he puts it:

“The simple social intercourse created when people rub shoulders in public is one of the most essential kinds of social “glue” in society.” — from A Pattern Language

When a shopping street is well designed, it becomes a magnet, attracting commerce and people from other neighborhoods in a city.

In contrast to well-developed shopping streets, undeveloped alleys can be dangerous and dirty places filled with garbage cans and populated by derelicts. How can well-designed shopping alleys improve livability and shopping streets?

How Can Alleys Improve Shopping Streets?

The Royal Mile in Edinburgh.

Shopping streets tend to grow at their ends. The Champs-Élysées is an extreme example, stretching over a mile in northwestern Paris from the Arc de Triomphe to The Place de la Concorde near the Louvre. As shopping streets stretch out, the average distance between two stores on the street increases and the street loses its sense of being a compact place to walk and shop.

[pullquote]As shopping streets stretch out, the average distance between stores increases and the sense of a compact area for shopping is diminished.[/pullquote]The main street is the prime real estate and focus of foot traffic. When shopping streets extend sideways to adjacent streets to become shopping districts, there is typically a large drop in foot traffic compared to the main street.

Insights from Optimal Foraging Theory

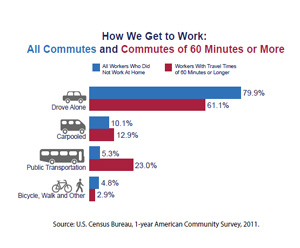

We can model shopper behavior using optimal foraging theory. Arising from research in ecology, the theory says that organisms forage in a way that maximizes their net energy intake in each unit of time. To model shoppers in this way, we assume that shoppers will seek areas with the most opportunities for buying attractive goods and services in each unit of time.

Example of an undeveloped alley.

Human shopping behavior has much in common with ancestral patterns for hunting and gathering. As a thought experiment, imagine an early human heading off to a berry patch to gather food. The patch is an attractive destination since much food can be gathered in a short time. Suppose that on the path back from the patch there is a walnut tree. A quick side trip enables harvesting additional food.

[pullquote]A well-designed shopping alley enhances foraging by bringing many small shops into view from a shopping street.[/pullquote]Insights about shopping streets from foraging theory address two points of view. One view is that of the optimizing shopper who goes directly to a destination for a particular item, and also who prefers shopping in a “rich patch” in order to pick up a few things. The second view is that of the shop keeper, who wants to design a place that attracts shoppers. Because the total traffic is the sum of shoppers who come for specific things (the “berries”) and those who are attracted by something they see while foraging (the “walnuts”), shop keepers find an advantage in having their shop be in a rich patch for foraging. To optimize business, they need foot traffic and a means to attract people walking by.

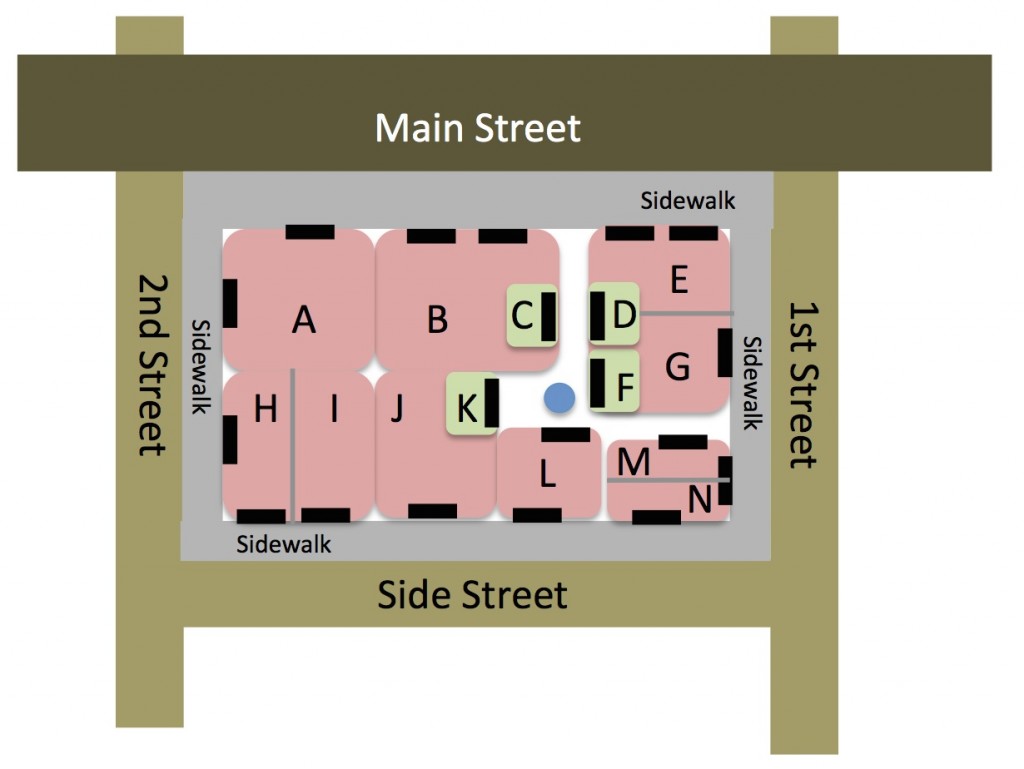

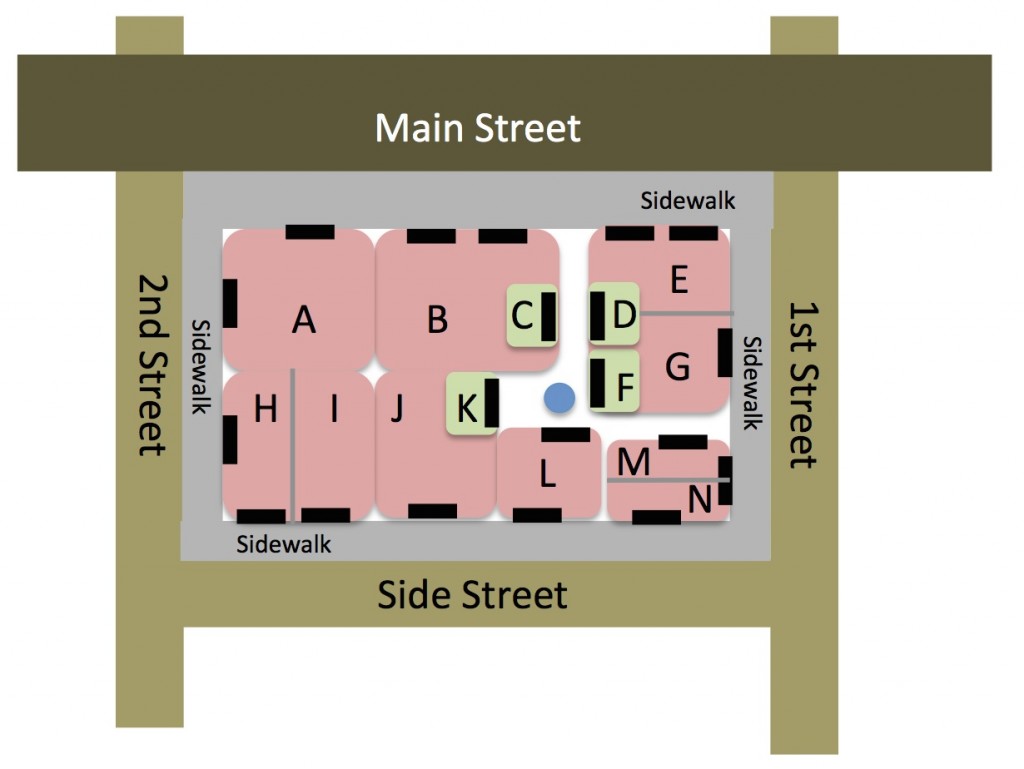

The alley (in white) can bring small stores C, D, and F within view and easy walking distance for shoppers on Main Street.

Consider how a developed shopping alley brings a variety of small shops into view from a main street. In the figure above, walkers who stay on Main Street would go by stores A, B, and E in order. The shopping alley (shown in white) brings stores C, D, and F within ready view and easy walking distance. It invites us to explore them. Exploring a shopping alley is much easier than walking around the block to more remote stores. Stores C and D off Main Street are more visible and visited than stores H, I, J, L, M, and N on the cross streets or side streets.

Because they invite exploration of many options in a short time, shopping alleys provide a richer foraging experience than a simple main street.

Elements of Attractive Shopping Alleys

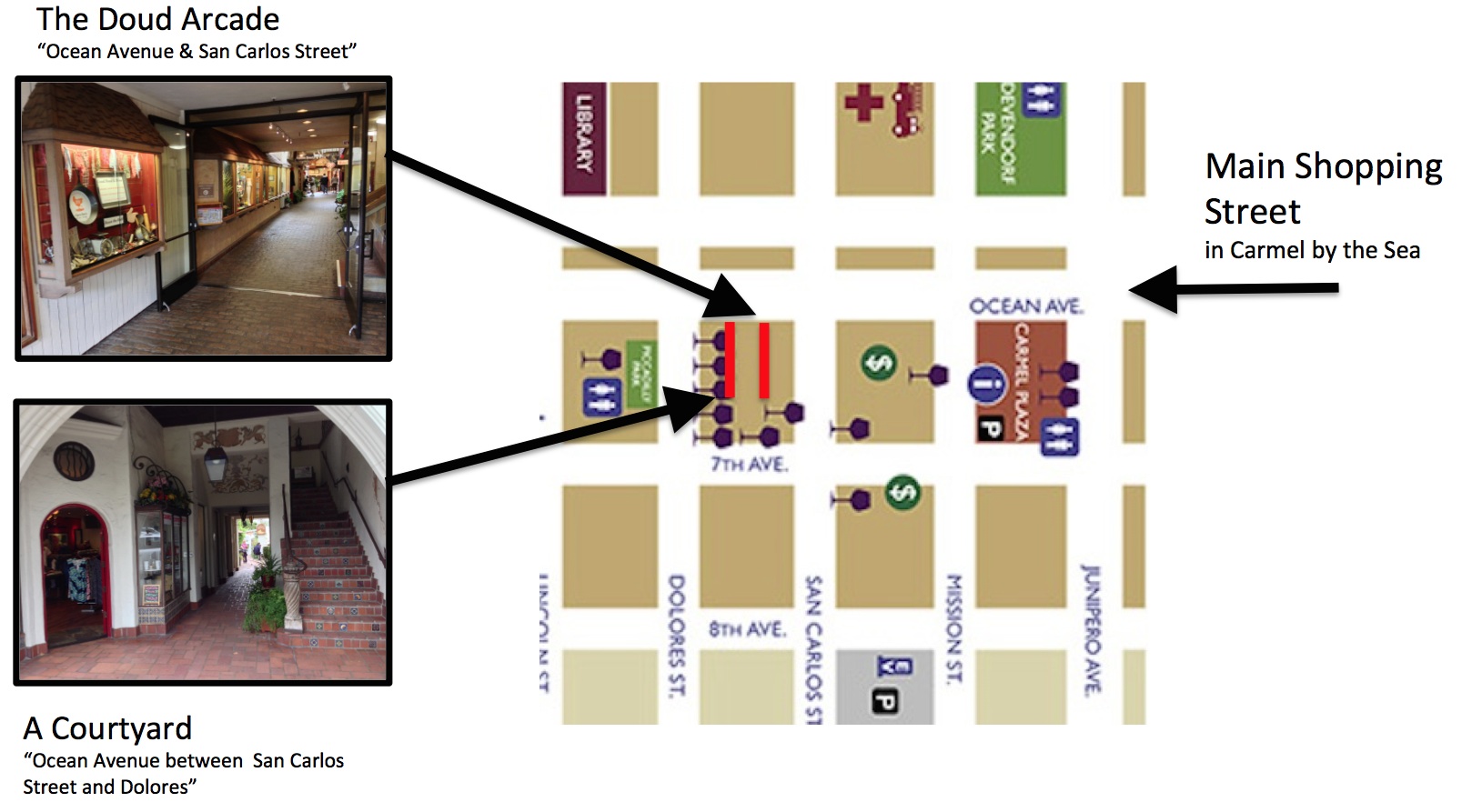

[pullquote]A shopping alley increases the density of attractive shops and improves the foraging experience.[/pullquote]A shopping alley provides a rich opportunity for foraging. Consider the Doud Arcade in Carmel, California shown in the first photo above. The arcade opens off Ocean Avenue, which is the main shopping street in Carmel. The arcade has skylights. Lighted displays of goods and store windows on the alley’s exterior walls attract people to alley stores. Compare this photo to the undeveloped alley above in Palo Alto, California, where shoppers walk quickly by hurrying to the next interesting offering on the street.

As a tourist destination in California, Carmel has developed Ocean Avenue to enhance the town’s appeal. The diagram above shows both Doud Arcade and a courtyard on the same block. The restaurants and stores on these shopping alleys are more accessible for foraging than stores on 7th Avenue which is the next street over.

As a tourist destination in California, Carmel has developed Ocean Avenue to enhance the town’s appeal. The diagram above shows both Doud Arcade and a courtyard on the same block. The restaurants and stores on these shopping alleys are more accessible for foraging than stores on 7th Avenue which is the next street over.

El Paseo (The Walk) in Sonoma, California.

El Paseo (meaning “The Walk”) in Sonoma, California, is a shopping alley off the main square shopping street. Like the Doud Arcade in Carmel, the entrance has signs and decorations intended to attract walkers to explore as they encounter it on the main street.

Paisley Close on the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, Scotland.

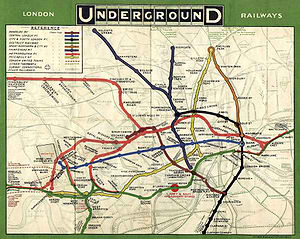

The Old Town of Edinburgh, Scotland, is the oldest part of Scotland’s capital city. The Royal Mile is the main artery and shopping street that runs down from Edinburgh Castle. Many small alleyways — courts, entries, and wynds branch off the road. These are generically called closes. Some of them lead to museums, stores, restaurants and other points of interest. Closes tend to be narrow, although many of them open up to courtyards. Paisley Close shown on the left leads to a Celtic Craft Centre.

Unimproved alley in the old town of “Mayfield.”

Alleys in many towns are a carry over from earlier times when they were used for deliveries and trash pickup. In Mountain View, California and the California Avenue area of Palo Alto (originally the town of Mayfield), alleys lead to parking lots a block off the main street. In such areas the potential of alleys is just being recognized. Development as shopping alleys would require remodeling underused sections of buildings in order to provide space for small shops.

The elements of “bad alleys” are well known. They may be dirty and unpaved. They may have garbage cans. Beyond the obvious cosmetics, successful shopping alleys are arranged so that people on the main street can see at a glance what they have to offer. At a minimum they have signage about the stores or restaurants. Beyond that they may have windows into the stores or lighted displays of goods available down the alley. In the main, the successful shopping alleys enrich the forage experience of walkers by giving them an easy way to get a sense of what is available on a short side trip.

Renewing Alleys as Public Spaces

Evening music in a new public space in Palo Alto created from reworked alleys and new construction.

[pullquote]Many cities are developing all kinds of alleys to improve urban livability.[/pullquote]Seattle, Chicago, Palo Alto and many other cities are re-developing all kinds of alleys to bring vitality to their neighborhoods and to improve urban livability. As in the Palo Alto photo on the left, downtown alleys and new construction have been combined to create public areas that are now a vibrant part of the night life.

In Seattle, the Alley Network Project is working with neighbors, businesses and community groups to revitalize alleys. They studied how neighborhoods in the U.S. and abroad have revitalized their alleys. A group at the University of Washington Green Futures Lab developed The Seattle Integrated Alley Handbook: Activating Alleys for a Lively City to help people re-imagine their alleys and make them lively, healthy, safe and environmentally friendly.

In San Francisco, The Linden Living Alley offers a book that describes design patterns for alleys. They have found that revitalized alleys not only improve shopping and livability, but they can also provide spaces for incubating cottage industries. The Downtown Denver Partnership is making plans to revitalize alleys along Denver’s famous 16th Street Mall. In Chicago, the Green Alley Handbook documents the city’s plans for managing alleys, handling waste water and heat issues, and generally making neighborhoods in the city more livable. In New York, the Voices celebrates the alley with a back street history of New York communities.

Applying Shopping Alley Principles to Smart City App Design

View above fountain from the Spanish Steps (Piazza di Spagna) in Rome.

Even though alleys are so small, the principles behind their design patterns can inform design for smart cities.

Alley renewal projects recognize and make use of existing city resources. In the same way, although there is much news about experimental smart cities and the trend toward mega-cities, most projects for smart cities in the next decades will be retrofitting and renewal. We are challenged to recognize the resources already present and to incorporate them into a vision of renewal.

As Christopher Alexander put it, shopping streets and other pedestrian ways provide a setting for much of our social glue. The enjoyment that people experience in these areas contributes to a sense of livability for neighborhoods. As in the photo from the Spanish Steps in Rome, people go to shopping streets to see and be seen. When we are on a shopping street, we see friends, we see what people are doing, how busy it is, whether the restaurants and shops are open, and so on.

Consider the two adjacent cities Palo Alto and Menlo Park on the San Francisco peninsula. In the evening, Palo Alto is alive with coffee shops and restaurants. People walk about in groups and couples. They pitch deals and discuss business over laptops everywhere at tables on the sidewalk at coffee houses and restaurants along University Avenue. Although Santa Cruz Avenue in Menlo Park has a number of stores and restaurants, except near El Camino Real it is much quieter on most nights. As a friend quipped, “They roll up the sidewalks in Menlo Park”.

[pullquote]Increasingly we use apps as our lenses for seeing things at the scale of cities. But there are too many of them and they do not convey a sense of place.[/pullquote]Other than by going there, if you did not know the peninsula and were looking for a place to dine or shop, how could you anticipate this difference between the cities? Increasingly we use the virtual world and social media as lenses for seeing things at the scale of cities.

There are dozens of apps for cities in many urban centers. There are apps for finding parking, apps for finding restaurants and making reservations, apps and web pages for finding out about stores, apps to guide travel by car, bus, or bike, apps for local news, apps for community participation, and so on. But that’s actually the problem. Such a pile of apps does not convey a sense of place.

[pullquote]At the scale of cities, an app should support foraging at the next level — finding attractive neighborhoods[/pullquote].Looking at patterns of well-designed shopping alleys provides some design hints. Shopping alleys make it easy to get an overview. They invite us to explore. At the scale of cities, an app should support foraging at the next level — finding attractive neighborhoods. It needs an intuitive interface that tells us about the following:

- Where are the neighborhoods?

- What kinds of stores and restaurants are there?

- Are stores open now or closed?

- Are the public spaces busy or deserted now?

- Are there any events happening now or shortly?

- What is the buzz about in this area?

- How can I best get there?

- Do I need reservations for dinner, a show, or parking?

- If I want to shop, how can I quickly get a sense of selection and pricing?

Top designers of apps and web pages bring an understanding of information foraging theory to their designs. The theory says that people rely on “information scent” or context of nearby information to help them navigate and choose which links to click. The design challenge is to create an app for exploring information about smart cities that is as easy and efficient as walking on a shopping street. Such an app would encourage people to explore their city like they explore their neighborhoods.

The Challenge

Cafe Borrones in Menlo Park in the afternoon.

[pullquote] The design challenge is to provide foraging and social experiences at city scale as natural as walking on a shopping street and exploring its shopping alleys.[/pullquote]Many people point to European cities built before cars became prevalent as favorite places for pedestrians. As one of its customers said about Cafe Borrone’s in Menlo Park, you go there “because Europe is too far to go for lunch”. As a German colleague told me:

“Coming from Germany, I’ve always missed the pedestrian zone in German cities. They serve as the face of the city. You go there to see and be seen. Shops may or may not even matter that much. In some sense they just provide the (productive) excuse for everyone to go. Once you are there, you pay as much attention to other people as you do to the shops themselves. It’s the atmosphere that matters and vitalizes, especially on those first warm days in the spring when everyone is just smiling.” — Christian Fritz

[pullquote]We can use foraging theory to guide design of shopping alleys and apps, helping us to easily find places we love to go.[/pullquote]By following design principles that acknowledge foraging behaviors, we can revitalize cities with shopping alleys and apps. Optimal foraging theory challenges us to revitalize shopping streets with shopping alleys and public spaces. In a similar way, information foraging theory challenges us to create fresh designs for apps that invite us to explore and enjoy our cities beyond our familiar neighborhoods. There are already apps in many cities that tell us how to get there (driving, walking, or multi-modal). The challenge is to design apps as lenses that help us to optimize our time and easily find places we love to go.

This post was written by Mark Stefik and Barbara Stefik. Thanks to Leonid Antsfield, Dan Bobrow, David Cummins, Christian Fritz, Melissa Hart, Lawrence Lee and Ed Wu for comments and suggestions on earlier drafts.

A physical workplace offers affordances for informal interactions. Meetings around problem solving or idea development are open and attract opportunistic engagement. Consider a physical office workplace as in the picture. What are its affordances for:

A physical workplace offers affordances for informal interactions. Meetings around problem solving or idea development are open and attract opportunistic engagement. Consider a physical office workplace as in the picture. What are its affordances for:

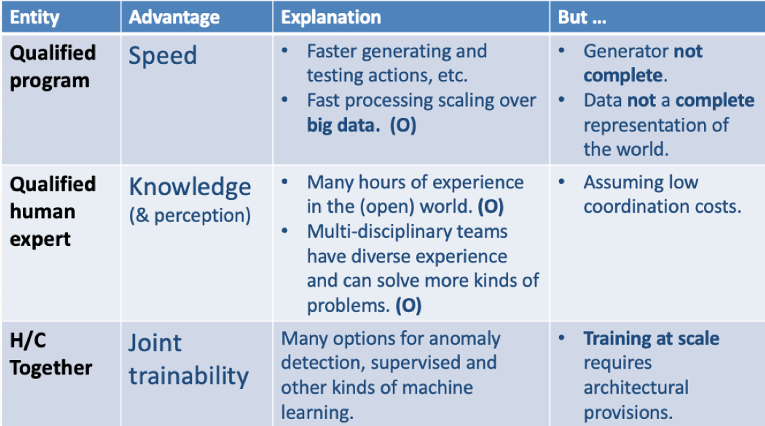

Enforcement organizations manage their activities in terms of shifts and beats. As in other jobs, shifts represent the hours that people work. Beats correspond to geographic areas in a city. The idea of “walking a beat” is traditional. Besides walking beats, there are also beats where officers use cars, carts, bicycles,

Enforcement organizations manage their activities in terms of shifts and beats. As in other jobs, shifts represent the hours that people work. Beats correspond to geographic areas in a city. The idea of “walking a beat” is traditional. Besides walking beats, there are also beats where officers use cars, carts, bicycles,

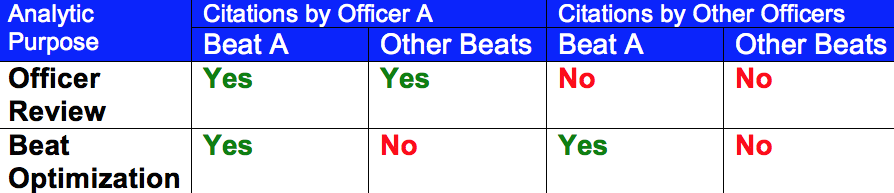

The proper answer depends on the question’s purpose.

The proper answer depends on the question’s purpose.