(page Under Construction)

Defining Sensemaking

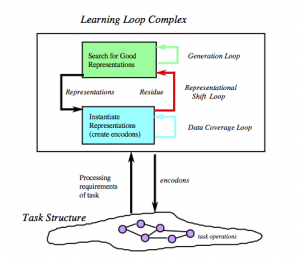

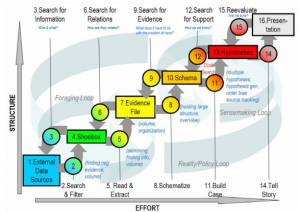

Wikipedia defines sensemaking as the process by which people give meaning to experience. In our 1993 paper Dan Russell, Peter Pirolli, Stu Card, and I define sensemaking as the process of searching for a representation and encoding data in that representation to answer task-specific questions.

Wikipedia defines sensemaking as the process by which people give meaning to experience. In our 1993 paper Dan Russell, Peter Pirolli, Stu Card, and I define sensemaking as the process of searching for a representation and encoding data in that representation to answer task-specific questions.

Today the term “sensemaking” is a well-known term of art in technologies and systems for analytics, big data, government funded research programs in intelligence analysis, and four related research areas characterized in a Wikipedia article as follows:

Sensemaking is the process by which people give meaning to experience. While this process has been studied by other disciplines under other names for centuries, the term “sensemaking” has primarily marked four distinct and somewhat related research areas since the 1970s: Sensemaking was introduced to Human–computer interaction by PARC researchers Russell, Stefik, Pirolli and Card in 1993, to information science by Brenda Dervin, organizational studies by Karl Weick and (narrative-based) decision support or Participative Narrative Inquiry by Darwent, Kurtz, Snowden and many others in 2004.

Sensemaking has been a recurring theme in my research.

Early 1990s — Beginnings

Dan Russell and I became intrigued when information technologies that we were crafting noticeably accelerated group processes. The groups were working to understand information in an area and creating information work products. I was intrigued by group processes creating outlines for papers in the Colab project in the setting of an electronic meeting room. Dan was intrigued by several technology examples for designing instructional courses at the Institute for Research on Learning. These courses ranged in topic from copier technology to algebra for high school students.

Dan Russell and I became intrigued when information technologies that we were crafting noticeably accelerated group processes. The groups were working to understand information in an area and creating information work products. I was intrigued by group processes creating outlines for papers in the Colab project in the setting of an electronic meeting room. Dan was intrigued by several technology examples for designing instructional courses at the Institute for Research on Learning. These courses ranged in topic from copier technology to algebra for high school students.

We wanted to understand the leverage points provided by the technologies and why they accelerated both understanding and production of the work product. We believed that the practice of representing concepts tangibly and digitally was important to the acceleration effects that we observed.

Peter Pirolli and Stuart Card joined us with more examples of the same accelerating effects. They also brought sensibilities of mathematical modeling to the understanding of what we were seeing. Two papers resulted from our collaboration. These papers introduced sensemaking to CHI and arguably began the research thread on information scent.

Russell, D.M., Stefik, M.J., Pirolli, P., & Card, S.K. The cost structure of sensemaking, Proceedings of INTERCHI, Amsterdam, Netherlands (ACM Press) April 1993.

Russell, D.M., Stefik, M.J., Pirolli, P., & Card, S.K. The cost structure of sensemaking, Proceedings of INTERCHI, Amsterdam, Netherlands (ACM Press) April 1993.- Russell, D.M., Stefik, M.J. 1993 The cost structure of sensemaking (long). Unpublished working paper, October 1993.

2000-2002 — Sensemaking White Paper

In 2002 I organized a “knowledge sharing challenge” at PARC to create a dedicated research area. With a group of PARC colleagues, we wrote a sensemaking whitepaper to map out challenges and opportunities for a research area.

In 2002 I organized a “knowledge sharing challenge” at PARC to create a dedicated research area. With a group of PARC colleagues, we wrote a sensemaking whitepaper to map out challenges and opportunities for a research area.

The group included Michelle Baldonado, Dan Bobrow, Stu Card, John Everett, Giuliana Lavendel, David Marimont, Paula Newman, Dan Russell, Steve Smoliar and several others. Our report surveyed industry developments, analyzed technological shifts and opportunities, and presented several organizing frameworks that we had studied. This white paper appeared just as the field of “knowledge management” was getting started. We found ourselves immersed in ideas from human-computer interaction, information retrieval, multi-media technologies, natural language processing, web technologies, and security technologies. At the same time, Nonaka and Takeuchi were attracting attention with their theories of organizational knowledge creation.

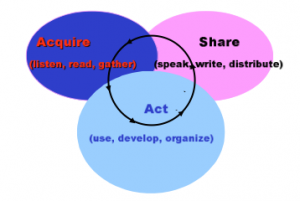

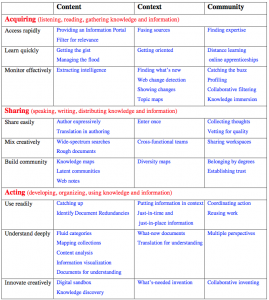

One of the products in the white paper was a table (on the left) of potential value propositions for sensemaking technology.

One of the products in the white paper was a table (on the left) of potential value propositions for sensemaking technology.

<– Click to enlarge.

It was organized according to three main parts of our analysis in terms of Acquire, Share, and Act.

We were fascinated by ways that technology could change and amplify how we think and work. In this exercise, it became apparent that we were by no means the first group to look at the social processes of knowledge generation. Although our frameworks for describing sensemaking have evolved with our projects, the foundation of analyzing activities for organizing and using information has been a foundation for all of this work.

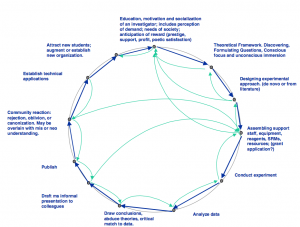

One analysis (on the right) by Joshua Lederberg came from his preface to Annual Reviews in 1989. He called it a twelve-step process for scientific experimentation or “epicycles of scientific discovery.” This same cycle was influential in framing a technology plan for national collaboratories.

One analysis (on the right) by Joshua Lederberg came from his preface to Annual Reviews in 1989. He called it a twelve-step process for scientific experimentation or “epicycles of scientific discovery.” This same cycle was influential in framing a technology plan for national collaboratories.

Stefik, Mark, et. al. The knowledge sharing challenge: The knowledge sharing challenge: sensemaking whitepaper. PARC working paper, 2002.

Stefik, Mark, et. al. The knowledge sharing challenge: The knowledge sharing challenge: sensemaking whitepaper. PARC working paper, 2002.

2002 – 2008 Sensemaking with Intelligence Organizations (NIMD)

World events triggered a burst of research and development on sensemaking. The attack on the World Trade Center and other places on September 11, 2001 brought our of attention to apparent failures of intelligence analysis. In addition, conditions were changing rapidly in the economy and in our local PARC environment. The 2002 recession, the bursting of the dotcom bubble, and other factors led to Xerox Corporation spinning PARC out as a subsidiary.

World events triggered a burst of research and development on sensemaking. The attack on the World Trade Center and other places on September 11, 2001 brought our of attention to apparent failures of intelligence analysis. In addition, conditions were changing rapidly in the economy and in our local PARC environment. The 2002 recession, the bursting of the dotcom bubble, and other factors led to Xerox Corporation spinning PARC out as a subsidiary.

My role organizing a small group of researchers on sensemaking and knowledge management was interrupted as PARC and Xerox leadership changed. I found myself leading the Information Sciences and Technologies Laboratory and spending most of my time overseeing this effort. This confluence of factors led us to responding to a call for research proposals connected to U.S. intelligence organizations, specifically the NIMD (Novel Intelligence from Massive Data) program from ARDA (now IARDA).

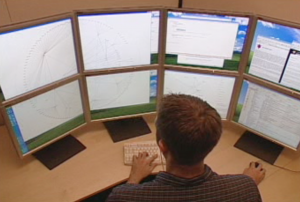

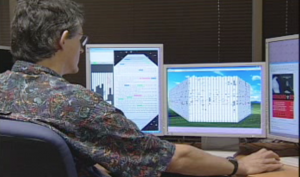

We had multiple awards and projects with ARDA. This enabled us to pull together researchers in visualization, user interfaces, and natural language in integrated sensemaking projects. Researchers on the projects included Patrick Baudisch, Dan Bobrow, Stu Card, Francine Chen, Lance Good, Jeff Heer, Ron Kaplan, Laurie Kartunen, Jock Mackinlay, Annie Zaenen, and Polle Zellweber as well as colleagues like Jeff Cooper and others from SAIC and Richards Heuer. We exploited advances not only in our own analytic and natural language processing technologies, but also new display technologies to create stunning and animated analyst workspaces.

We had multiple awards and projects with ARDA. This enabled us to pull together researchers in visualization, user interfaces, and natural language in integrated sensemaking projects. Researchers on the projects included Patrick Baudisch, Dan Bobrow, Stu Card, Francine Chen, Lance Good, Jeff Heer, Ron Kaplan, Laurie Kartunen, Jock Mackinlay, Annie Zaenen, and Polle Zellweber as well as colleagues like Jeff Cooper and others from SAIC and Richards Heuer. We exploited advances not only in our own analytic and natural language processing technologies, but also new display technologies to create stunning and animated analyst workspaces.

With our colleagues at SAIC, we engaged with several intelligence analysts to understand the analytic process, to build several prototypes, and to run sensemaking experiments. With Richards Heuer, we built particularly lightweight tool for analysis of competing hypotheses that is described as a separate project.

With our colleagues at SAIC, we engaged with several intelligence analysts to understand the analytic process, to build several prototypes, and to run sensemaking experiments. With Richards Heuer, we built particularly lightweight tool for analysis of competing hypotheses that is described as a separate project.

Below are some examples of information visualizations produced by the lab during this period.

Selected Publications

- Pirolli, Peter. Information Foraging Theory: Adaptive Interaction with Information. Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Zellweger, P.T., Mackinlay, J.D., Good, L., Stefik, M., Baudisch, P. 2003 City Lights: Contextual Views in Minimal Space, CHI

- Stefik, M. The New Sensemakers, Red Herring

- Good, L., Bederson, B.B., Stefik, M., Automatic Text for Changing Size Constraints

- Jean Scholz. Report on 2008 Sensemaking Workshop

- Papers from 2008 workshop xxx

- We Digital Sensemakers 2011 We Digital Sensemakers scan

- Focusing the light 1999 Focusing the Light Internet Edge

Later Sensemaking Projects

Sensemaking has become an integral part of many information systems, including many systems in big data and analytics.

- Social indexing (Kiffets personalized news)

- Social Music

- Enforce

- Collaborative Analytics

Patents

My patents on sensemaking systems started issuing in 2006.